It is market wisdom that smart option traders buy cheap options and sell expensive options. And indeed, we frequently see that the ideal option to buy will be extremely expensive (and thus risky), despite the high probability of price movement. Indeed, the entire concept of covered call writing is built around that core principle: selling overpriced (overvalued) options to those who ignore this principle.

Stock Price and Its Effect on Option Values

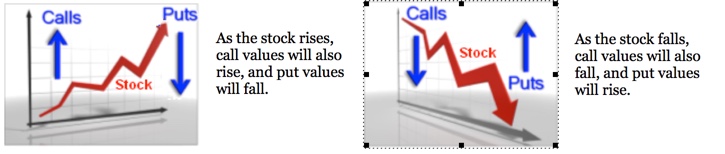

Of all the elements affecting an option’s value, discussed in the previous article, none is more significant than stock price. Since stock options bought to open universally are bought to either speculate on the stock’s movement or to hedge against the movement, it is natural that an option’s value will move as a result of changes in stock price. The following graphics illustrate these relationships:

This is simple enough. Call values move in the same direction as the stock, and put values move inversely (opposite) to the stock price. The amount of change in an option’s price will be determined by the option’s delta – explained further on. One who thinks a stock will imminently rise would buy a call to speculate on it; if bearish, a put would be the purchase of choice.

Buying Options

Other than to close a short option position, traders buy stock options for two primary reasons: to hedge an existing stock position, or to speculate on the direction of the underlying stock. Those who expect the stock to go down will buy puts, either speculatively or to hedge a long stock position. Those who expect the stock to go up will buy calls, either speculatively or to hedge a short position in the stock.

| Option Buy | Speculator’s Orientation | Hedger’s Goal |

| Buy puts | Bearish – believes stock headed down | Long – protect a stock position |

| Buy calls | Bullish – thinks stock is headed up | Short – protect a short stock position |

Because stock options can be bought for a fraction of the cost of the underlying stock, yet give the holder the right to buy (calls) or sell (puts) the underlying stock at any time through expiration, they give the holder leverage over the underlying shares for the life of the option.

Example: If you pay $100,000 for a six-month call option to buy Southfork ranch for $5,000,000, you essentially control Southfork for the option period, for a nominal sum. This is leverage. The owners of Southfork cannot sell the property to anyone else until your option expires. You can exercise the call at any time, sell the option or let it expire – it’s your choice. Unexercised, the call will expire worthless.

Speculating on stock direction by purchasing options is an old game, and it can work quite well. The problem is that the stock must make the desired move before expiration. Thus the option buyer must get both the direction and timing of the stock move right.

Selling Options

Traders sell stock options primarily to generate income. The strategy used will be dictated by whether one is bullish/neutral or bearish (list omits option spreads):

- Bullish/Neutral: sell covered calls to generate income

Time value premium produces returns even when the stock itself is flat - Bearish: sell calls naked to capitalize on stock’s failure

Lets trade go to expiration or repurchases calls at a profit when stock pulls back - Bullish/Neutral: sell OTM puts as an alternative to a covered call

Naked put writing creates income, the OTM strike reduces assignment risk - Bullish: sell ATM or even ITM puts to acquire stock at discount

The put premium reduces the stock cost if assigned; pure profit if not assigned

Buying Options – Strategy

Speculators buy stock options primarily to speculate on an anticipated movement in the underlying stock, since the option will gain in value as the stock moves. Speculators don’t buy options when they have a neutral outlook on the stock, so the strategy used is dictated by whether one is bullish or bearish.

- Bullish: buy calls to capitalize on expected stock rise

ITM call is most expensive but gains in price at highest rate with stock’s rise

ATM call is the best value, but doesn’t move dollar-for-dollar with the stock

OTM call is cheapest but statistically the worst buy - Bearish: buy puts to capitalize on expected stock fall

ITM put is most expensive but gains in price at highest rate with stock’s fall

ATM put is the best value, but doesn’t move dollar-for-dollar with the stock

OTM put is cheapest but statistically the worst buy

| Figure 3.3 Stock Price Movement: | |||

| Stock Rises | Stock Falls | Time Passes | |

| Call Buyer | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Call Seller | Negative | Positive | Positive |

| Put Buyer | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| Put Seller | Positive | Negative | Positive |

The table preceding indicates the various effects on option buyers sellers posed by a rise or fall in the stock and by the passage of time (time decay).

As explained in more detail in a subsequent article, delta measures how closely the option’s price moves with the stock price. If the option’s price moves dollar-for-dollar with the stock, the option’s delta is 1.0 for a call and -1.0 for a put. If the option moves only $0.50 for a dollar move in the stock, the delta is 0.50 for a call and -0.50 for a put.

Thus for example when the stock is $45, the 50 Call might cost only $1.00, but with a delta of 0.30 the stock would have to move to about $53 in order for the call price to double. Obviously, the stock has to work much harder (move further) to create profitability for the ATM or OTM call buyer. The more time value the buyer paid, the more the stock must move.

Not all long options are speculative. Options are also bought to hedge an opposing position. For example, one who is short the stock might buy a protective call to assure the ability to buy the stock at an acceptable price should the trade go wrong (stock goes up). Or one who is long the stock might buy a protective put to assure the ability to sell the stock at an acceptable price should the stock fall.

Time Value

It is critical for anyone writing covered calls or making any kind of option-based trades to understand time value and its importance. For the option writer, time value is one of the major sources of return (the other is profit from opportunistically trading options as the stock moves). But for the option holder, time value is a negative because it decays and picks his pocket as time passes. In other words, in order for a long option position to win, the option buyer first must recoup the time value before the trade can become profitable. For example, if when the stock is $50, the trader pays $2 for the current 50 Call, which is ATM and thus all time value, the breakeven point is $52 (50.00 strike price + 2.00 time value). The holder who exercises the call must sell the stock for $52 to recoup the calls’ cost, and only the amount received above $52 will be gain.

It is often said that time is the option writer’s friend and the option buyer’s enemy. This is true, because time value decays at a predictable rate as time elapses.

Time Value in Short Calls

In the covered call, returns are generated by the time value portion of the premium. Assume that we bought a stock for $50 and wrote the 45 Call on it for a $6.00 premium. That is a fat premium, but we are obligated to sell the stock for $45 if called. The time value is only $1.00 (6.00 – 5.00 of intrinsic value). The following table illustrates how time value works:

Figure 3.4

| Time Value in Calls – the Profit | Per Share |

| Buy shares of stock | – 50.00 |

| Sell DEC $45 Calls | + 6.00 |

| Cost Basis (breakeven) | – 44.00 |

| Sell stock | + 45.00 |

| Profit (Loss) | + 1.00 |

If called out at $45, our profit will be the $1.00 of time value, despite that huge call premium, because we are selling the stock at a $5.00 loss.

Time Value in Long Options – and How It Is Forfeited

Suppose that instead of buying the stock we had purchased the 45 Call at a cost of $6.00. The call gives us the right to buy the stock – now trading at $50 – for $45. Deducting out the $5.00 of intrinsic value from the calls’ cost, we paid $1.00 in time value. But if the call instead is exercised, the time value is thrown away:

Figure 3.5

| Forfeiting Time Value in Long Calls Stock = $50 | Per Share |

| Buy DEC $45 Calls | – 6.00 |

| Exercise calls to buy stock | – 45.00 |

| Sell stock | + 50.00 |

| Profit (Loss) | – 1.00 |

This trade resulted in a $1.00 loss. By exercising the call, the holder forfeits the time value. Time value for the option holder truly is a “use it or lose it” proposition. Whenever an ITM call or put has time value, the holder forfeits the time value upon exercise. Had the option holder instead sold the calls for $6, the time value would have been retrieved. Even selling the calls for $5.50 would have yielded a better result than forfeiting all the time value.

The only way for the option holder to retrieve the calls’ time value is to sell the option, and the closer expiration approaches, the more time value will decay. This illustrates why ITM calls are not exercised before expiration so long as they still have time value. But once time value is gone or nearly gone, it is no longer an impediment to early call exercise and the call writer can face early assignment at any time. If the call trades below parity (below intrinsic value), early exercise becomes even more likely.

Long Option Economics

Here is a very important point about the economics of buying options: at some point the option holder must either sell or exercise the ITM long option. Otherwise, the option will expire worthless. Assume as in the above example that a writer paid $6.00 for a $45 call when the stock is $50. If the holder takes no action by expiration the calls will expire worthless, resulting in the loss of the entire premium paid. If the stock still is at $50 when expiration rolls around, rather than take a $6.00 loss, the holder could exercise the 45 Call to buy the stock for $45 and sell it at $50, which reduces the loss to $1.00, as shown in the time-value forfeiture example above.

If the stock has remained at $50, then close to expiration the call holder could roll the calls out to the next month by selling the current call for its $5 of intrinsic value plus any remaining time value and buying the next month’s 45 Call for approximately $6. The cost of the roll would be an additional $1 or so of time value (actually, the difference between current and next-month time value for the calls), but rolling the calls out keeps the trader in the game and avoids forfeiting the calls’ intrinsic value. Instead of taking a $1.00 loss, then, the trader could instead use the same $1.00 to roll the calls out one month.

Needless to say, OTM options are never exercised even at expiration, since it would be far more advantageous to simply buy or sell the stock at market.

The author has no position in any of the stocks mentioned. Financhill has a disclosure policy. This post may contain affiliate links or links from our sponsors.